Does the fact that you have stepped on a fumie mean that you are an unbeliever? Can you really choose between stopping someone’s torture and keeping your own hands clean? And most importantly, Rodrigues finally believes that God had spoken to him and shown him the way, that by apostatising, he has become a true Christian and is saving his brethren from death.

And also something which really drives home and makes you think about what it must mean to have true faith.

But what Endo has done is something I hadn’t expected. I was expecting Rodrigues to die at the end of the novel. SPOILER ALERT (click and highlight to see text) And this is where his real struggle begins. And there he comes face to face with the man he has come to Japan to find, his teacher Ferreira. You are there with Rodrigues as he jumps from one painful situation to the next, always shadowed by his Judas, the wretched, weak apostate Kichijiro, until he is finally captured himself. For the first time they have met men who treated them like human beings. The reason our religion has penetrated this territory like water flowing into dry earth is that it has given to this group of people a human warmth they never previously knew. It is a struggle from the beginning as most Christian converts are from the lower orders of the social hierarchy many are peasants who are struggling with poverty and whose lives are hellish.įor a long, long time these farmers have worked like horses and cattle and like horses and cattle they have died. He is perpetually caught between wanting to end the suffering of the Japanese Christians and staying true to his vocation, that he must continue his mission to spread and uphold his faith in Japan. Rodrigues is constantly treading water, at the edge of desperation, as he sees his flock captured, forced to step on fumie and apostatise, tortured and killed. I don’t think I have ever come across another novelist who has managed to do this in such a searing portrayal of a man struggling against fear and doubt and still trying to do justice to his vocation. My reading of Silence as a non-Christian will probably differ from those who do believe, and yet, I feel that Endo successfully manages to get to the root of what he is trying to portray and shows the reader the real, honest and true anguish of someone who is trying to understand what it means to have faith and to live their life in a true and meaningful way. Via Macao, they board a ship to a village near Nagasaki and there, their ideas and views on their vocation and the land they had dreamt of comes under increasing attack as they realise that the path they have chosen is harsher than anything they ever expected. It is in this harsh period of forced apostasy and danger that the Jesuit priest Sebastian Rodrigues and his companions set out from Portugal to discover the fate of their teacher, Christovão Ferreira, who has disappeared in Japan after rumours of his apostasy sent shock waves across the Christian world. But the Tokugawa Shogunate, fearing the growing popularity of Christianity amongst the country’s poor and the possible fomentation of anti-government sentiment, has closed Japan’s doors against outsiders, leading the country into self-imposed isolation and declaring a ban on Christianity. It is almost 60 years after Francis Xavier’s successful mission to Southern Japan. Like The Samurai and The Volcano, it is a study of Christianity in early modern Japan and the terrible path it carved through the lives of its believers and those who tried to stamp it out.

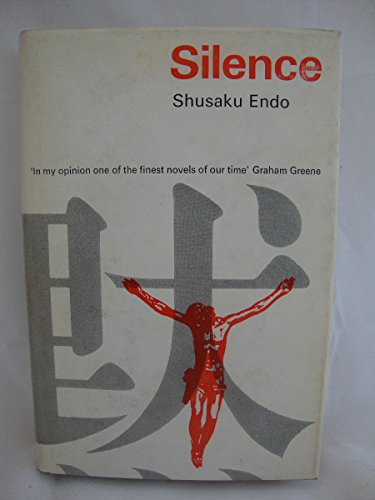

Shusaku Endo’s Silence is probably his most famous novel.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)